Tony Kofi had a workplace accident when he was 16 years old. Despite never having learned to play a musical instrument, he had a vision of himself playing one as he fell from a great height.

He went on to become a well-known saxophonist as a result of the experience.

Tony, who was three floors high, realized what a lovely day it was. The sky was calm and clear. Tony recalls, “I was really thrilled.”

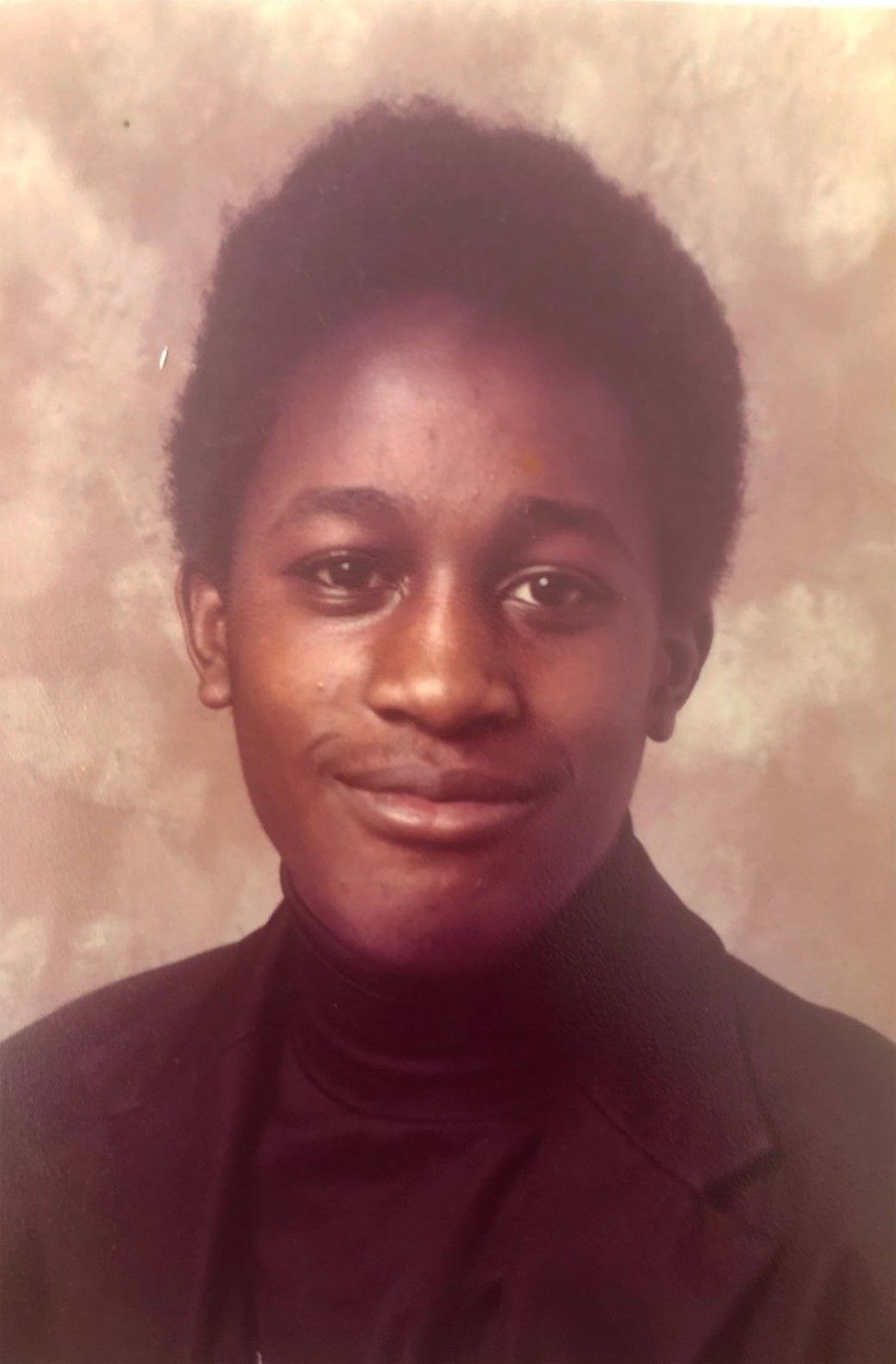

Tony Kofi, 16, was working as a carpentry apprentice in spring 1981, assisting in the replacement of a house’s old roof.

He’d asked his supervisor if he might work while his boss ate lunch since he was so eager to impress. He’d been cautioned by his boss to be cautious.

He was chopping down a two-by-four. Tony remembers, “I didn’t see it fully and it shattered.”

“It grabbed my sleeve and knocked me out.”

Tony began to lose consciousness.

His initial reaction was that he had little chance of surviving. So he just relaxed, let go, and closed his eyes, he claims. ADVERTISEMENT

“I’m not sure if it’s adrenaline or what – since I’ve heard that everything slows down when you fall from a tremendous height,” he explains. “I’ve only recently begun to glimpse flashes of pictures. It was incredible.”

Tony’s visions took him to many locations across the world, as well as the faces of individuals he didn’t recognize.

“I saw little youngsters I’d never seen before — I suppose they were going to be my offspring.” And the image of me rising up and playing an instrument was the one that stayed with me the most. ‘This is the strangest feeling I’ve ever had,’ I thought.

“And that was the end of it; I was completely blacked out.”

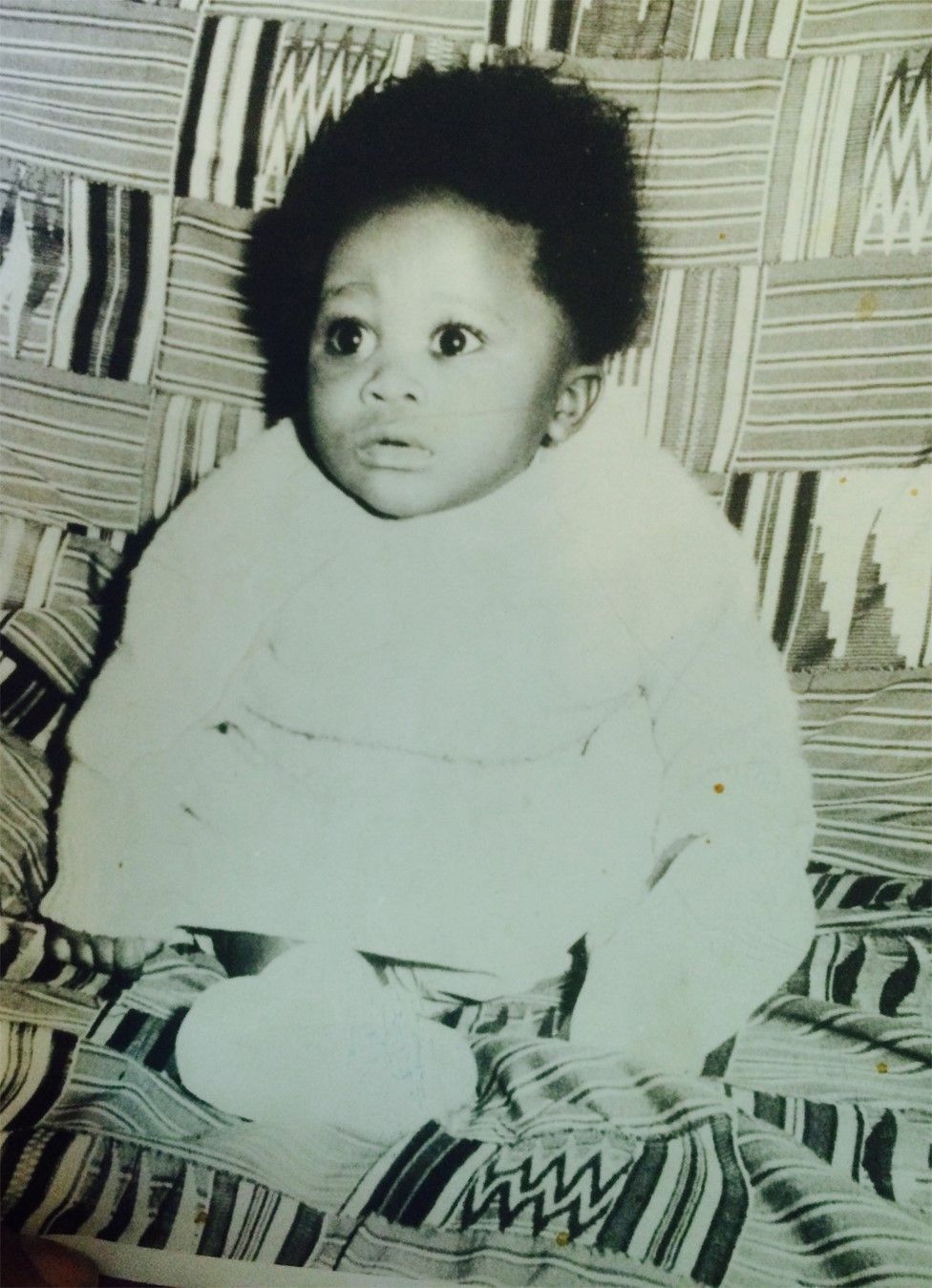

The smooth, smokey tones of jazz performers flowed across Tony’s boyhood home in Nottingham in the 1960s. Ama, Tony’s mother, was listening to her albums.

Ama and her husband Jack were from Kumasi in southern Ghana, where she had heard American jazz singer and trumpeter Louis Armstrong play live during his 1956 visit to the nation. She had fallen in love with jazz as a result of it.

In his early 20s, Jack spent time in England following his boxing career, and in 1959, he relocated his family to Nottingham permanently. A year later, Ama and their two sons arrived with a collection of records, and the home was filled with synchronized jazz beats.

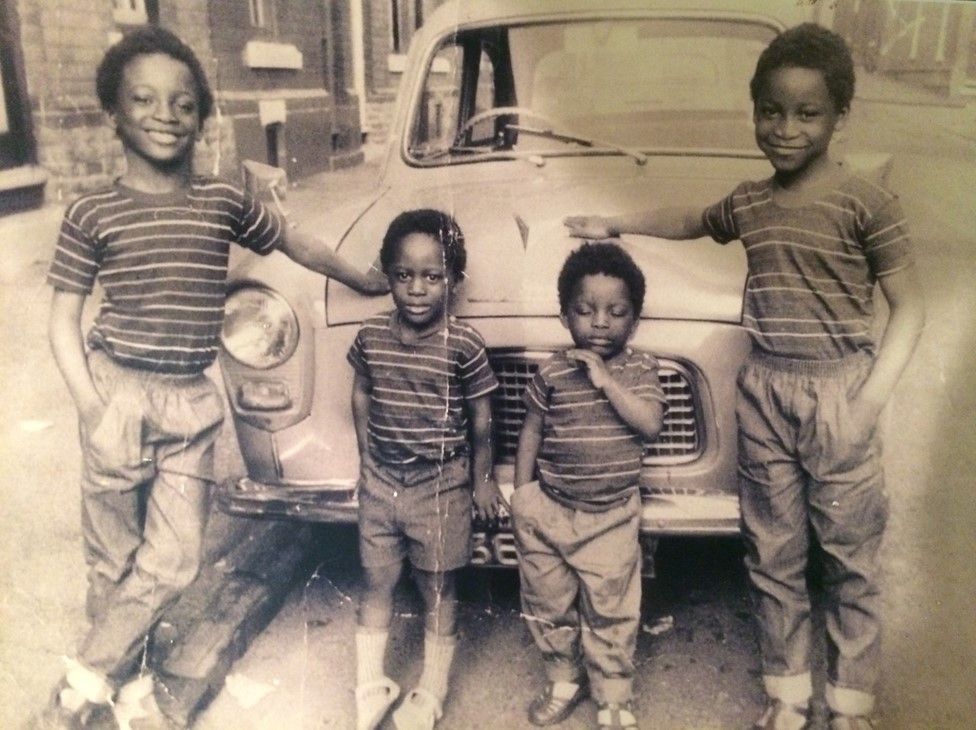

Tony was the fifth child of Ama and Jack, who had a total of seven sons. Born in 1964, his childhood recollections are as “sky blue and clouds of white” as Armstrong’s famous song What a Wonderful World.

“I can barely remember winter as a kid,” he adds, “since I was too busy having fun to care about these gloomy, chilly days.”

He grew up eating Ghanaian food and listening to Ghanaian music, and he characterizes his background as “extremely traditional.” “English was for outside,” his parents said, insisting that the family speak Twi, a Ghanaian dialect, at home. Tony, though, was a “tearaway” in primary school.

“I was born left-handed, and in Ghana, if you have a left-handed child, you are expected to make him right-handed,” he adds. It’s a long-standing custom, and my parents demanded that I learn to write right-handed.”

The school was notified. They had to double-check that I wasn’t writing with my left hand, which I believe made me a little unruly since I was going against the grain.”

Tony had little interest in anything other than sports, football, and playing with his pals during his early years at school. He expressed an interest in music in high school but was told he wouldn’t be able to pursue it.

“They gave you small exams and then they decided who was more focused and grounded,” Tony explains, “and I wasn’t one of the ones chosen.”

“I was devastated, but then they hid me in the woodwork, so I simply accepted it and carried on like that throughout high school.”

Tony was getting better at his profession and dropped out of school in 1980 to work as a carpenter apprentice, going to college one day a week and studying on the job the other four days. One of these positions was where he had his tragic accident.

Tony awoke in the hospital after the accident, with his mother, father, and two brothers at his bedside, all anxious and wondering how he was doing.

“I replied, ‘My head hurts,’ and they answered, ‘You scared us, you’ve been out for days.’”

Tony was told that he had struck his head so hard in the fall that he could have died from the impact. He was disoriented, bruised, and had significant head damage.

He recalls his job supervisor paying him a visit when he was in the hospital.

“You just fully hit the bottom on your head like a sack of potatoes,” he told me.

Tony came home to recuperate three to four weeks after he was well enough to leave the hospital. He had been compensated for his injuries and lost wages, and his work had been left available for him to return to whenever he was ready.

The pictures he’d seen while falling, though, refused to fade away and continued “flashing back” whenever he closed his eyes.

“They tormented me,” Tony adds, “because it was almost like I was being shown something.”

He kept it to himself, but the fall had permanently changed his perspective on life.

Tony, who had never studied music, began to consider investing his settlement money in a musical instrument.

But what had he seen in his visions as the instrument? He was looking through music books when he came across a description of a gleaming brass woodwind instrument with a conical form.

The saxophone was the final piece of the puzzle.

“I’m not saying I was musically illiterate back then,” Tony recalls, “but I’d never seen a saxophone.” “I’d undoubtedly heard it on the radio, but I was utterly unaware of it.”

Tony bought his first saxophone for £50 in early 1982, which was a lot of money in the 1980s and around £200 now. He returned to his family’s house, clutching his musical heirloom.

Tony’s mother gave him a weird look, oblivious to what Tony had seen in his vision.

“I replied, ‘It’s a saxophone, and I’m going to learn how to play it,'” Tony adds. “I’m going to resign from my position.”

Tony recalls his mother placing her palm on her brow and requesting that her husband Jack talk to their kid.

Tony recalls her telling Jack, “He’s wasting a very excellent trade.” “It’s likely that he’s afraid of what happened in the autumn.”

Tony refused to talk to his father, despite his father’s best efforts.

“‘I can’t go back,’ I said. “If I go back, I would as well have perished in that fall,” I told them.

Tony couldn’t afford lessons, and his mother and father couldn’t afford to spend their “hard-earned money” on music lessons, as Tony puts it, so his mother offered him something even more important — vinyl gold.

Tony recalls, “She gave me the piles of albums.” “She said, ‘Look, this is very, very wonderful music; utilize these albums, learn from them,’ and I did.” I taped them, put on my headphones, and listened to them over and over again, attempting to learn from them and play along.”

So Tony decided to teach himself how to play the saxophone, but his first attempts did not generate the saxophone’s signature mellow, seductive tone.

Squeak, screech, shriek.

Tony describes it as “like a five-year-old child attempting to play the violin.” The sound was terrible and “ear-piercing.”

His brothers took on the role of “musical barometer” for him. Suddenly, the door to his bedroom would burst open, and a shoe would slam into Tony, striking him on the head or back. But he continued to practice for two hours, five hours, and eventually eight to ten hours a day.

The flying shoes got less common over time, and his brothers began to remain and listen to Tony play.

Tony recalls his mother remarking to him one day when she came up a plate of meals to his room, “I understand what you’re playing… This song is one of my favorites.”

Take the “A” Train was a piece from an album by jazz pianist and composer Duke Ellington.

The song is about a train rushing down a New York subway line into Harlem’s Sugar Hill area.

Tony, too, felt as though his life was on track. He recalls, “It was a fantastic moment to be me.”

Tony could not read music and wanted to learn more about music theory, despite the fact that he could play the saxophone by ear. He applied to a college in Nottingham, which is known for its music and performing arts training, in 1986-1987, but was informed he couldn’t get a place since he hadn’t finished any musical grades or tests.

“It was almost like that rejection again,” he recalls, “but this time I wasn’t going to accept it because I’d found something I truly, deeply loved and wanted to pursue, and that rejection had just strengthened me.”

While reading about the life of jazz artists in an American magazine called Downbeat, he came across several advertisements for music institutions in the United States.

Tony explains, “I simply chose one and thought, ‘You know what, I’m going to write to them and attempt to apply,’ and that’s precisely what I did.”

He applied to Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, which is known for its musical brilliance. Berklee graduates have earned 311 Grammy awards to date.

“They auditioned me first, but they finally took me,” Tony recounts, and in 1988, at the age of 24, Tony headed off to study music in America, terrified and eager.

He was awarded a Berklee scholarship because, according to him, he was “quite excellent” for a self-taught musician. Tony received some assistance from fundraising efforts and his parents when the story appeared in the Nottingham newspapers.

“By that time, they were extremely happy and impressed that I’d stayed with it and established a name for myself,” he adds.

“When they found out I’d been accepted into Berklee College of Music, they were all like, ‘Wow, this isn’t a joke, this is serious,’ and I did tell my parents about the visions at that point.”

They accepted that this was the best course for their son, according to Tony.

At Berklee, he had a “wonderful” experience. Musicians from all over the world came to learn the art of jazz at the academy. Some, like Tony, were self-taught, while others were classically schooled.

He explains, “They took my turning up there as the most regular thing.” “However, in England, my birth country, it’s almost as if you have to go through a system to be recognized.”

When he returned to England, he began work on his debut album, All I Know, which won both the parliamentary Jazz Award and the BBC Jazz Award in 2005.

“I recall having the music in front of me for the first tune we recorded, which was called Boo Boo’s Birthday by [American jazz composer and pianist] Thelonious Monk,” he adds. We listened to my first attempt, and I thought to myself, “You know what, it sounds like I’m reading off a hymn sheet.”

“I simply thought to myself, ‘OK, I’ve got to get back to where I feel at ease, where I started.'” So I tore up the music, tossed it in the trash, and simply performed five choruses of pure bliss, and that’s how I recorded the entire album, with no music.”

Tony serves as a teacher at The Julian Joseph Jazz Academy and The World Heart Beat Music Academy in addition to being a performer, songwriter, and bandleader. He began teaching at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in September 2020, and Nottingham University gave him an honorary professorship this year.

He enjoys working with both young and old musicians, motivating them to pursue their ambitions and never give up hope.

But what about the other pictures he saw as he plummeted from the roof – the many locations across the world and children’s faces?

According to Tony, they’ve also come to life.

“I am a grandfather and the father of three lovely children,” he says. “Well, it’s all happened, and I’ve been all over the world. I had the opportunity to collaborate with some of the best musicians in the world.”

Macy Gray, Harry Connick Jr., and the Julian Joseph All Star Big Band are among those who have performed at these events.

Tony frequently encourages his pupils to play by ear rather than using written music in his lessons. He describes the sensation of doing this as “totally free.”

“It’s like riding a bike with stabilisers, and you’re using these stabilisers to stay balanced,” Tony explains. That’s what it feels like when you take the stabilisers off and see how the youngster rides with so much freedom.”

He’s taking Louis Armstrong’s counsel to heart: “Never play the same thing twice.”

WRITTEN BY : @MZZTAKENDRICK

![Strongman – Scars [Performance Video] Strongman - Scars [Performance Video]](https://www.ghanasong.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Strongman-Scars-Performance-Video-150x150.png)